When Samuel Maddock built a browser that lets friends watch an online video at the same time, he used what seemed like the cheapest and simplest option: Chromium, a free, open-source version of Google’s Chrome web browser.

Maddock’s creation worked well, but because it was based on Chromium, he needed another Google product called Widevineto authenticate users and prevent video piracy. He sent Google a request, outlining the project, and waited. And waited. Four months and 10 emails later he got a one-line answer: sorry, you can’t use the software for that.

Google headquarters in Mountain View, California.

Photographer: Michael Short/Bloomberg

He wasn’t doing anything illegal. In fact, using Google’s secure-streaming tool would have ensured his project was above-board. But the internet giant withheld access, without saying why. Maddock gave up on making a browser soon after.

“You have these gatekeepers like Google that decide which projects can work and if you’re not granted that permission you’re screwed,’’ Maddock said.

This is one small developer working on a small project. But his story demonstrates how Google’s dominance of the browser market -- and the underlying technology tools -- gives the company far-reaching control over how the web works, and who gets to create new ways of accessing it.

It’s another example of how the Alphabet Inc. unit’s power has grown to the point where regulators from India to the European Union are looking for ways to keep it in check. The EU has already fined Google for breaking antitrust laws in the markets for online search, display advertising and mobile operating systems. Chrome is an important cog in Google’s digital ad system, distributing its search engine and providing a direct view for the company into what users do on the web.

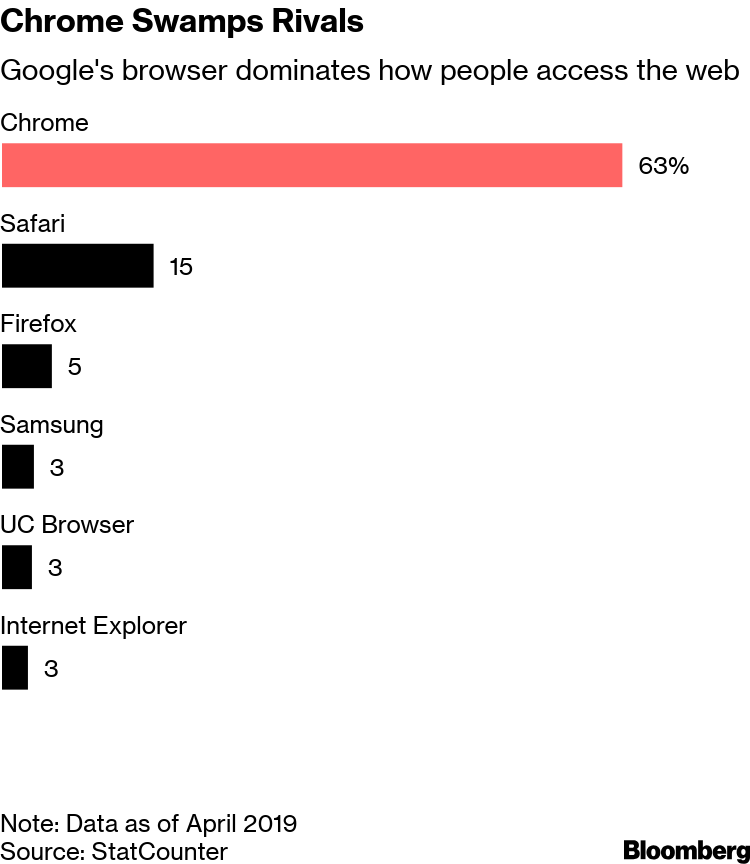

Few home-grown Google products have been as successful as Chrome. Launched in 2008, it has more than 63% of the market and about 70% on desktop computers, according to StatCounter data. Mozilla’s Firefox is far behind, while Apple’s Safari is the default browser for iPhones. Microsoft Corp.’s Internet Explorer and Edge browsers are punchlines.

Google won by offering consumers a fast, customizable browser for free, while embracing open web standards. Now that Chrome is the clear leader, it controls how the standards are set. That’s sparking concern Google is using the browser and its Chromium open-source underpinnings to elbow out online competitors and tilt entire industries in its favor.

Most major browsers are now built on the Chromium software code base that Google maintains. Opera, an indie browser that’s been used by techies for years, swapped its code base for Chromium in 2013. Even Microsoft is making the switch this year. That creates a snowball effect, where fewer web developers build for niche browsers, leading those browsers to switch over to Chromium to avoid getting left behind.

This leaves Chrome’s competitors relying on Google employees who do most of the work to keep Chromium software code up to date. Chromium is open source, so anyone can suggest changes to it, but the majority of programmers who approve contributions are Google employees, and any major disagreements get settled by a small circle of senior Google employees.

Chrome is so ascendant these days that web developers often don’t bother to test their sites on competing browsers. Google services including YouTube, Docs and Gmail sometimes don’t work as well on rival browsers, sending frustrated users to Chrome. Instead of just another ship slicing through the sea of the web, Chrome is becoming the ocean.

“Whatever Chrome does is what the standard is, everyone else has to follow,” said Andreas Gal, the former chief technology officer of Mozilla.

Google didn’t target Mozilla in overt ways during Gal’s seven years at the company. Instead, he described it as death by a thousand cuts: Google would update Docs, or Gmail, and suddenly those services wouldn’t work on Mozilla.

“There were dozens and dozens of ‘oopsies,’ where Google ships something and, ‘oops,’ it doesn’t work in Firefox,’’ Gal said. “They say oh we’re going to fix it right away, in two months, and in the meantime every time the user goes to these sites, they think, ‘oh, Firefox is broken.’’’

Google has tried to mitigate this problem. It has a separate project focused on making different browsers behave in more uniform ways so website developers have less tweaking to do. And the company has advocated for more public standards that can be followed by all browsers.

“We take it seriously, the responsibility of being good stewards of the web,’’ said Darin Fisher, a vice president of engineering on the Chrome team. Google’s business relies on the web working for as many people as possible, so the company doesn’t have an interest in squashing competition, he said.

0 Comments